First published in Creek Freak, Indian Creek Climbs in 2018.

Climbers aren’t the first to experience what this amazing valley has to offer. The Creek’s history starts long before technical rock climbing existed.

Hunter-gatherers visited this area 10,000 years ago. In the last 2,000 years, Native Americans (Indian Creek was the southern limit of the Fremont culture and the northernmost outpost of the Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloans) moved in on a more permanent basis and settled in Indian Creek year-round, growing corn, beans, and squash. After a peak around 1100-1200, they declined in number, possibly due to drought, resource depletion, and perhaps even incursions from early Navajos (Diné).These early residents were gone by the mid-1300s, though they left behind an abundance of rock art, dwellings, pottery shards, moki steps, and other evidence of their presence. The Diné appeared not to have settled in Indian Creek, but were occasional/seasonal visitors from 1300 onwards. Newspaper Rock, famously, contains petroglyphs from every era, from Anasazi glyphs so old that the chiseled rock has almost regained the natural varnish color, all the way to people on horseback (horses are a recent European import).

In 1859 the Macomb Expedition traversed the Indian Creek area, exploring, mapping and looking for the confluence of the Colorado River and Green River. They found the area to be uninhabited. The first Anglo settlement began soon after, with ranching following close behind. Don Cooper and Mel Turner settled along Indian Creek in 1885. By 1900, they and several neighbors joined forces and created the Indian Creek Cattle Company. The company has changed hands a few times over the years and is now owned by the Nature Conservancy and run by the Redd family. The headquarters are at the Dugout Ranch outside the Needles District—right in the middle of our glorious playground. Please respect their work and privacy. Please keep your dog on a leash and under control, especially while around the cattle.

It took a long time for rock climbers to discover Indian Creek. In contrast, Shiprock, the 1,800-foot-tall volcanic plugin New Mexico, was climbed in 1939. This was quite a feat for David Brower and crew, involving the first use of bolts for protection on a big climb, and an innovative hauling system (for hauling people, not gear!). This was a one-off ascent; the sandstone cliffs and pinnacles of the Southwest were regarded as impossibly steep. Soon after, World War II halted domestic rock climbing.

By the mid-50s, Shiprock began seeing repeat ascents, its test-piece reputation was slowly dismantled, and a new generation began searching for new challenges. Were the sandstone towers climbable? Southern Californians Jerry Gallwas, Mark Powell, and Don Wilson wanted to find out. In March 1956 they ascended 800-foot-tall Spider Rock, and in May 1957 they (with Bill Feuerer) succeeded on the infamous Totem Pole. Distracted by the beginnings of Yosemite Valley’s Golden Age, the California climbers did not return to the desert. The big walls of Yosemite were opening up, Joshua Tree was being developed, and the climbers saw no need to drive to the Colorado Plateau to climb.

The next wave of desert climbers came from Colorado. In 1957, a young geologist from Boulder, Colorado named Huntley Ingalls was driving around southern Utah on a “gravity survey” intended to pinpoint locations where uranium, in high demand in the heyday of the Cold War, might be found. Ingalls hailed from Maryland and as a youngster, explored the pages of National Geographic, in the hopes that one day, if he was lucky and determined enough, he might actually visit some of the wonderful locations he saw in the magazine.

That summer, Ingalls visited Shiprock, Natural Bridges National Monument, The Needles area (long before Canyon-lands National Park existed) and Indian Creek, where he took note of the dramatic pinnacle of North Six Shooter. Of all the places he visited, it was the valleys northeast of Moab—Professor Valley, Onion Creek, and Castle Valley—where Ingalls discovered the most exciting rock formations. “Castleton and the Fisher Towers: I couldn’t believe them the first time I saw them... I thought they were just incredible.”

Back in Boulder, he tried to persuade his climbing partners and friends to attempt a sandstone tower, with little success. Finally, in May 1961, Layton Kor agreed, and they drove out to climb the best of the towers in Castle Valley—Castleton Tower. They were astonished by the quality of what they found. What was next? For Kor, aside from a quickie first ascent of the nearby Priest, with Fred Beckey and Harvey Carter, a couple days later, he became obsessed by Yosemite, and would not return to the desert for a full year. And for Ingalls? Ingalls was indifferent to the other formations around Castle Valley. He was intrigued by the obvious challenge of the adjacent Fisher Towers, but they appeared daunting and he wanted more practice. He knew, from his gravity-survey wanderings, where to find another rock spire equally as impressive as Castleton Tower: North Six Shooter, in the then-remote Indian Creek.

Indian Creek, at that time, was a quiet canyon of serene beauty. The Redd family grazed cattle, as they had for decades.One dirt road traversed the valley, and many days might go by without any cars driving through. In the spring of 1962, with Kor ensconced in Yosemite, Ingalls, Maurice Horn, and Jack Turner headed to Indian Creek.

The North Six Shooter climb went smoothly until the climbers reached a pedestal 25 feet from the top; here they were stuck under a crack-less face. They needed several bolts, but had already used the few they had brought. Turner recalls of the final, blank wall, “We just sort of stood there and looked at it...” The arrival of a sandstorm clinched matters, and the climbers fled back to Boulder. The next weekend Ingalls, Horn, and Steve Komito returned and summited. The 1962 ascent of North Six Shooter, via what they called the Southeast Chimney, 5.8 A2, marked the beginning of Indian Creek climbing. Five years went by before the second ascent, by Chuck Pratt and Steve Roper.

The year 1969 was an important one for Indian Creek. A few more climbers were coming to the desert to visit and ex-pore. South Six Shooter was climbed, by Bill Roos, Burnham Arndt, and Denver Collins. More significantly, Chuck Pratt and Doug Robinson climbed a new route on North Six Shooter. Driving out, Pratt, taking note of the myriad vertical cracks lining the canyon, made the timeless observation, “Future home of American crack climbing.”

Pratt’s vision was prophetic. But in 1969 there was no means to protect these pristine cracks, so climbing them remained a tantalizing fantasy. In the 70s, armed with Hexentrics, Jimmie Dunn bravely climbed several now-obscure lines in the Fringe of Death Canyon, including theY Crack. He also introduced Earl Wiggins, Ed Webster, and Billy Westbay to the perfection of what was to become SuperCrack of the Desert. Wiggins, Webster, and Dunn agreed, in theory, that this was a line so perfect as to be “worth dying for.” Wiggins tied in, set off, and they established three pitches to the rim in 1976. That same year, Jimmie Dunn and Brian Delaney ascendedGeneric Crack, also to the rim.

In January 1978, Wild Country began marketing “Friends.” At first, climbers did not fully grasp what they had been given, but as the early 80s rolled around, a growing number of aficionados understood the perfect match between the Indian Creek splitters and the new camming devices. Things would never be the same.

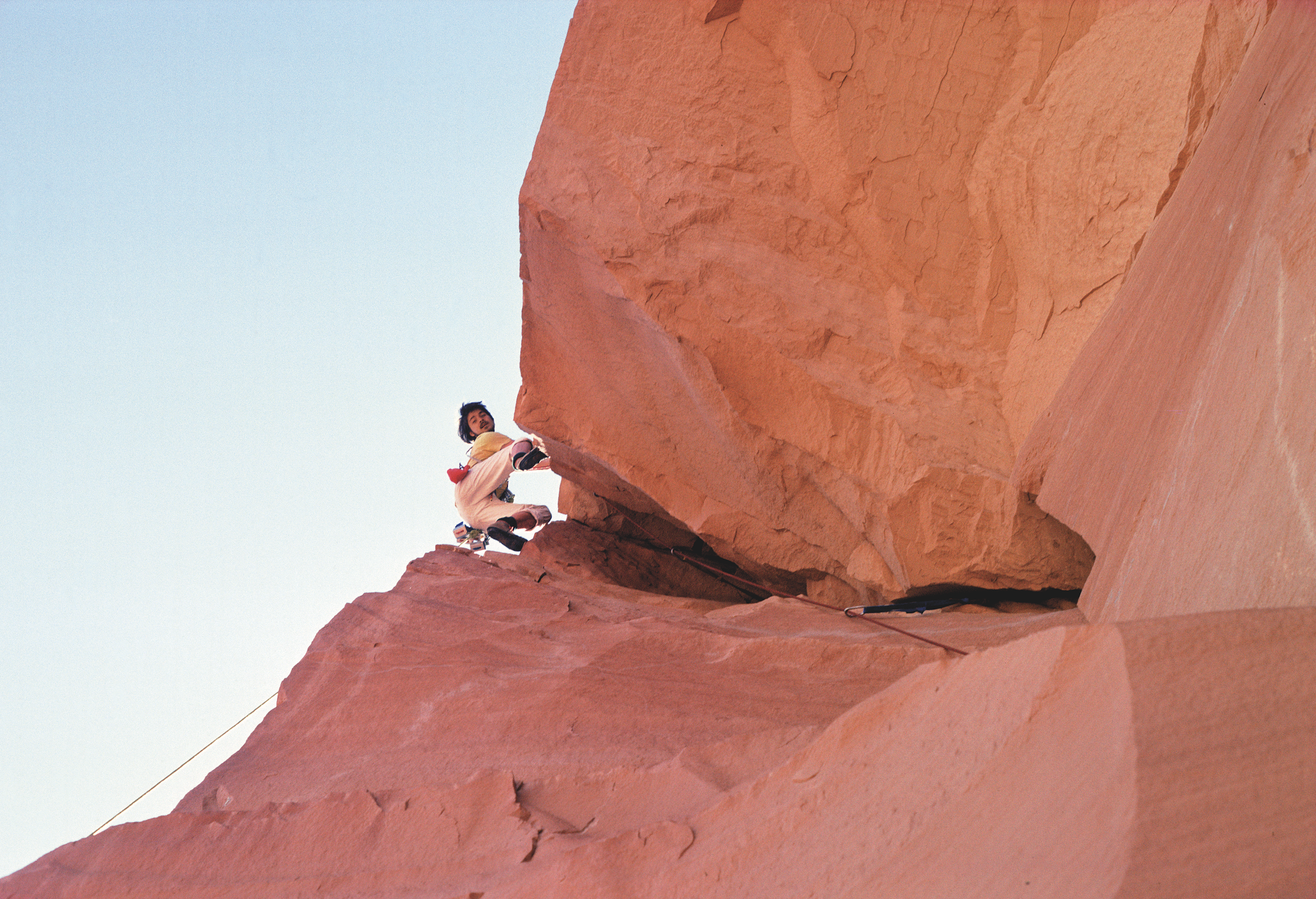

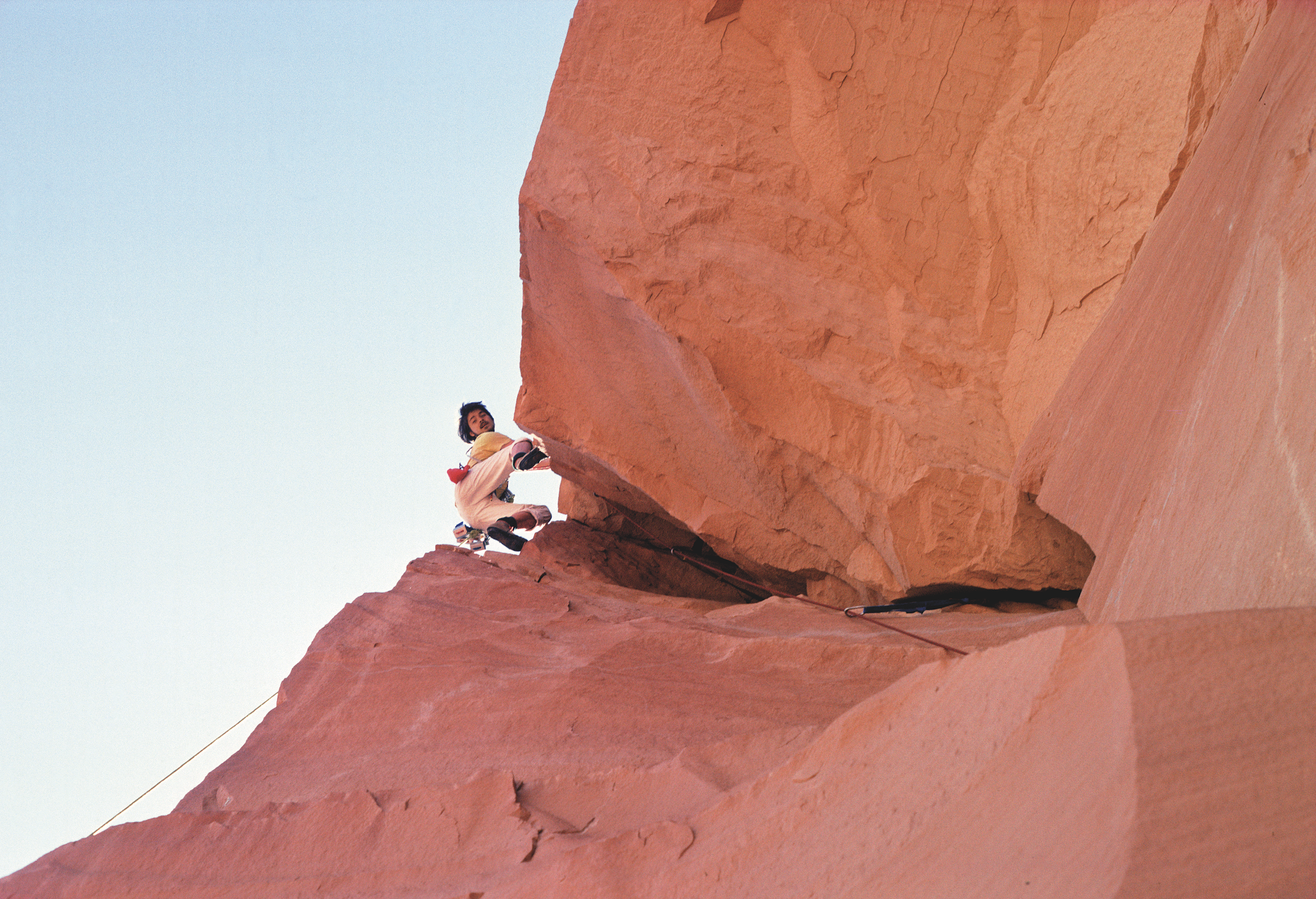

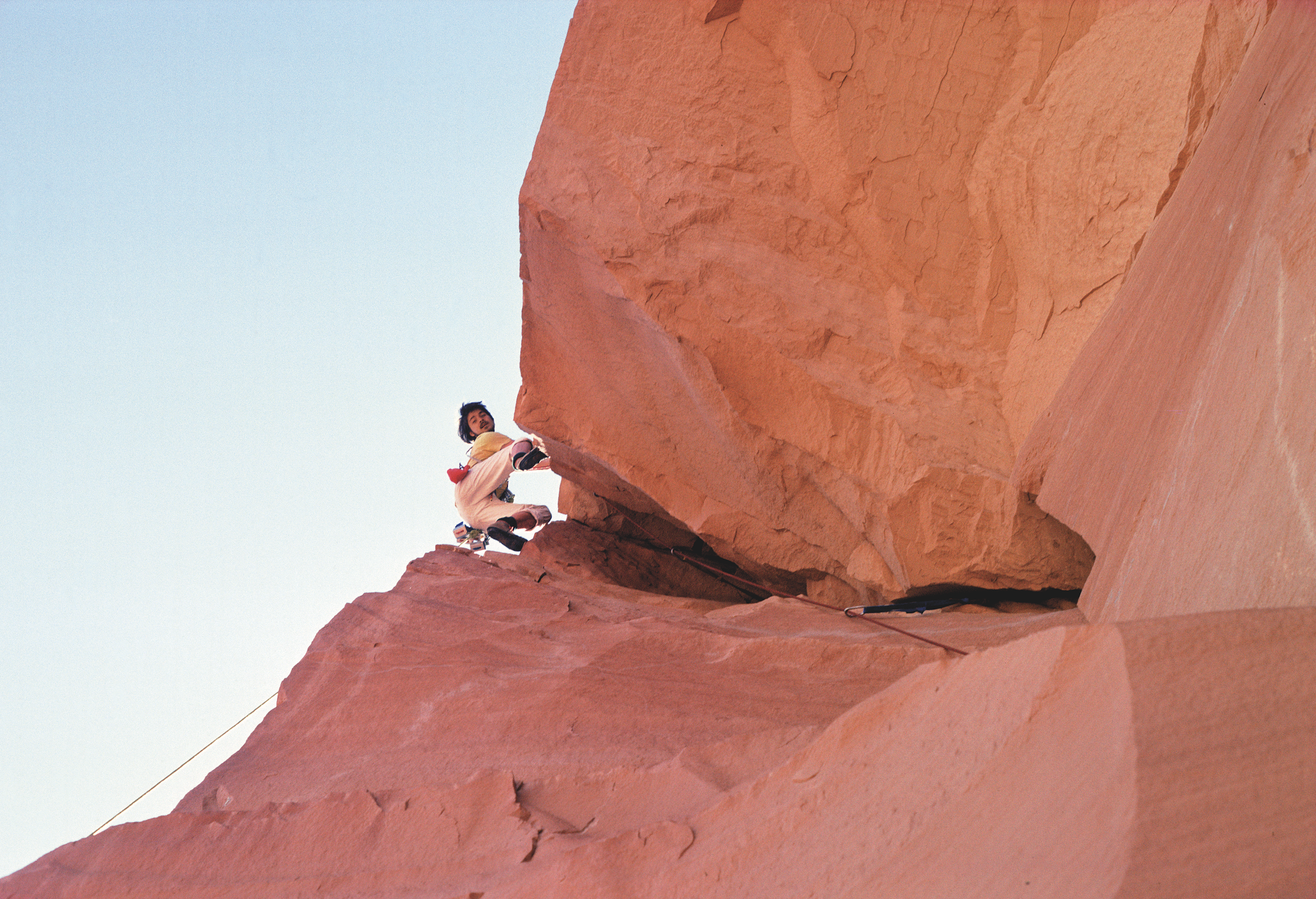

Steve Hong was one of the first climbers to fully exploit the possibilities of this new paradigm. While attending medical school in SaltLake City, he walked Indian Creek with binoculars, discovering and climbing line after line of five-star cracks. Along with partners KarinBudding, his brother Andy, the late Steve Carruthers, Bob Rotert, and many more, he went on a historic first-ascent frenzy. Steve is a gifted climber and many of his lines are still considered test pieces! Dr. Hong introduced an important piece of Indian creek history—plaques. After completing a route, he would etch the date and grade on a small tile of sandstone and leave it at the base. For the routes of which he was particularly proud, he would also engrave a name. This practice has been adopted by many first ascensionists and leaves an unobtrusive and enriching record of our history. Stumbling across a Hong plaque is discovering a piece of history. Forty years on from the invention of Friends, and many hundreds of climbs later, the story is ongoing.