The First Earth Day and the Advent of Clean Climbing

Posted by Fred Knapp / Jim Erickson on 22nd Apr 2020

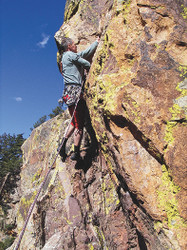

Today marks the 50th Anniversary of the first Earth Day. For climbing legend Jim Erickson, Earth Day served as a call to arms to eschew the use of pitons and cement the beginning of clean climbing. Below is Erickson's essay from the upcoming Eldorado Canyon: A Climbing Guide, 3rd edition by Steve Levin. A limited edition Earth Day cover features Roger Briggs on a clean ascent of Vertigo.

Jim Erickson:

Going Nuts

Development first, environment second, the de facto history of climbing and, indeed, Western civilization. The antithesis of the Leave No Trace ethic. Earth Day, in April 1970, was the first time that most Americans started thinking consciously about preserving the environment for future generations.

Every American rock climber for 50 years had followed in the steps of Continental European climbers and hammered pitons to protect their climbs. These pitons were then removed by the final member of the climbing party, for economic and aesthetic reasons. In parts of England and Wales, climbers had instead relied on artificial chockstones—or “nuts”—for protection.

I used pitons almost exclusively in my first 10 years of climbing, although I had been carrying a few token nuts since 1966. At the end of 1971, just after the FFA of The Naked Edge, I read an article about piton damage to the rock in Yosemite, with graphic pictures of Serenity Crack, and I unilaterally decided I did not want to be part of that rock damage any longer. I decided to stop carrying pitons on rock climbs. This decision was entirely motivated by environmental issues.

I asked my main climbing partners of the time to join me: Duncan Ferguson said yes; Steve Wunsch said no. (Steve joined us seven months later.) This was the beginning of what is now called “Clean Climbing” in America.

Duncan and I then sold all of our pitons. Everyone thought we were quitting climbing at first, and then thought we were crazy when we said we were going to do all of our routes and first ascents only with nuts. I patterned my new rack of nuts, in size and quantity, after my old rack of pitons. It started with the smallest nuts (#2 Stoppers and Peck knurled wires) up to a two-inch Dolt Super Chock.

Our first couple of climbs showed some flaws in our new protection systems. Many of the nuts we carried on four-foot slings around our necks, as the British climbers did, two or three to a sling. If you placed one of these, the other two were left behind on a sling and could not be used higher up. The short wired nuts on stiff wires would easily be pulled out if you climbed above them, we feared. To avoid this, Duncan would place a wire nut at the limit of his reach, clip a long sling to it, and then clip in his rope. By this time his overhead protection was below his waist.

Clearly, we needed a better system for wired nuts, one that was as short as possible but very flexible to prevent the nut from pulling out. This led to the “invention” of what is now called the quickdraw. My first ones used a short piece of 5/8-inch tubular webbing tied in a loop, making the total length about nine inches including the biners. These “Quickdraws” worked very well, and I carried three or four on my rack for the next 15 years.

In the spring of 1972 Duncan and I made the first serious attempt on pitch four of Jules Verne. I easily climbed up to the little roof, placed the bomber gear, and ventured up into the unknown. I climbed the first half of the crux and attempted to get a good #2 Stopper in to protect the final moves, but could not. I reversed back almost to the good gear, took a very short fall, and lowered back to Duncan. It was obvious that one blade piton placement would make it a very well protected pitch. Since Duncan and I were the only ones climbing solely on nuts, no one would have even blinked had we done it. But we had already drawn our ethical line in the sand, so we didn’t even consider placing the pin. We retreated.

Royal Robbins certainly deserves the credit for introducing nuts into the consciousness of American climbers in 1966. Nutcracker Suite (5.8) was, I believe, the first FA in America using nuts for protection. Duncan and I took nuts to the final level of commitment. It was a very big step. It was one thing to use nuts on a climb that was three number grades below the standard of the day, and quite another to use them on cutting-edge, on-sight first ascents.

It was relatively easy to judge a piton placement. The resistance to the hammer blows and the sound of the hammering gave a pretty good estimate of the strength. A quick sideways tap would confirm this. A nut placement was more subtle, and far more directional. We did not trust a single nut to catch a leader fall. Unless it was a very large nut dropped downward in a narrowing slot, we were deathly afraid that the nut would pull out as the climber fell by it or climbed above it, or that the tiny nuts would break or shear through their placements. Of course, British climbers in North Wales were well aware of the advantages and pitfalls of nuts, but these same climbers were also well known for their runout and poorly protected leads, and gave us little confidence.

In the spring of 1972, considering the style they were first led, the FFAs of Wide Country and California’s Insomnia Crack, and Duncan’s lead (sans Ament’s rest point, so in fact the first free lead) of Supremacy Crack, were North America’s state-of-the-art, nut-protected climbs.

I don’t recall my first fall onto a nut, but it happened in early 1972. It may have been that fall on Jules Verne, or one during an attempt on the FFA of Pony Express, a short fall onto a #2 Stopper. We eventually realized that well-placed nuts would not always pull out, and would hold short to moderate falls. This was not at all clear in the beginning.

—Jim Erickson