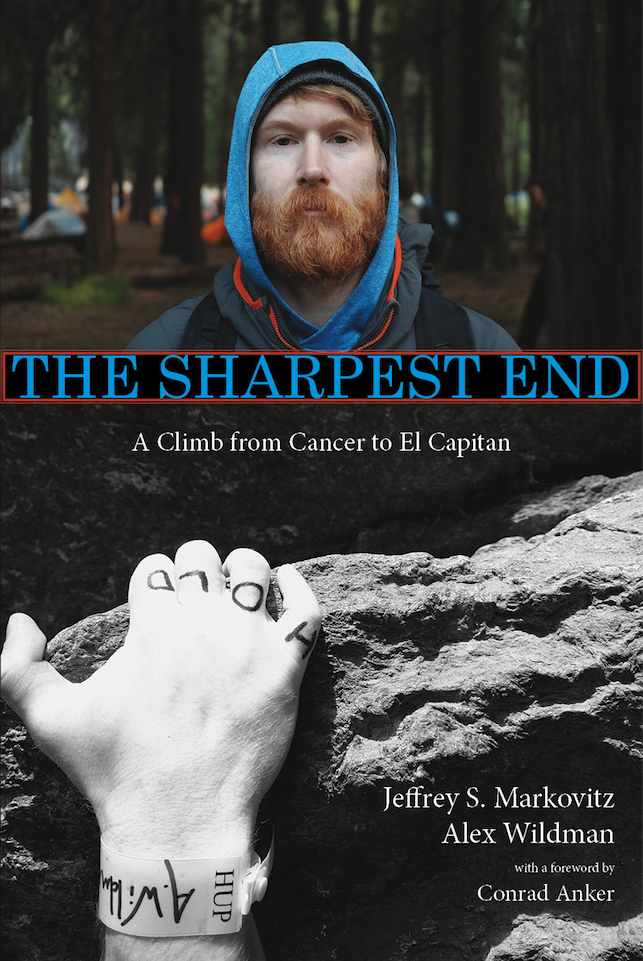

High Exposure | Excerpt from The Sharpest End

Posted by Jeffrey S. Markovitz and Alex Wildman on 28th Oct 2021

The scratch of charcoal whispered somewhere off to the right. A cleared throat. The strident screech of the stool’s metal legs across the floor made him blink, but it didn’t avert his eyes from the arête outside the window. He was naked in front of a room full of strangers.

The arête was made from two meeting brick walls of a Fishtown rowhome that rose two stories then ceded to sky. Alex followed the corner of bricks touching, past the archaism of telephone wires chaotically in route to the nearest time-worn wood pole, and found purchase in the afternoon blue. The sky’s time lapse seemed to mirror the slowness of his sitting there, the losing of his thoughts in the staring, the trying to overcome the awkward pressure of being there: a subject to be looked at and considered. A body. A body so ravished by chemo that he didn’t recognize it anymore, let alone like it. The thing that reflected back at him in any shiny surface was not a thing he knew. It was the thing that made him wear a hat all day, even to bed. It was the thing that had made him come to this small neighborhood in Philadelphia, to undress in front of strangers, to be objectified. To hope for completion by being taken apart.

The window was backlit by the afternoon, so Alex couldn’t see any example of himself in the panes of glass. He wondered what the others were thinking of him, exposed as he was in the center of their circle. Every sound seemed to signify some reaction, some epiphany, that forced one of their hands across space, into creation. He listened astutely. Maybe that one brushing meant something; perhaps that brief arching gesture he caught from the corner of his eye could tell him something. Something of what they thought.

“Losing my hair has been more difficult than expected,” Alex said. “Not only do I dislike how I look, but I feel like someone else. It’s easy to tell myself that losing my hair isn’t the worst thing in the world and I can rationalize how it isn’t that bad, but it’s something outside of my control and a choice that I never would have made.” As a timid kid growing up in New Jersey, and a redhead to boot, Alex was made fun of a lot. His flagrant red hair stood out like a candle’s flame amongst his peers, so naturally, they gravitated—moths—to it, to tease him for it. Testing his sensitivity by his reaction, his school-age counterparts pressed into this quality that seemed to make Alex so different. Eventually, that difference bred confidence, and Alex’s long red hair and lumberjack beard became a point of pride for him, a symbol by which he could assert his self-reliance and individual strength against the conformed monotony of the others. What his childhood peers harassed him about became the characteristic most closely associated with his adult identity and strength. It was also a social beacon: everyone knew that red hair.

But the chemo took that away from him. Like Samson, gone went his power. Bald, he was stripped of his iconic countenance and remanded to his childhood insecurity. Worse, he knew he looked like someone going through chemo. There was no way, in his daily life, that he could hide this fact; he knew everyone who looked at him had the immediate thought: that guy has cancer. For a lot of people, beyond the physical problems, cancer treatment causes depression. These things can hurt a person’s interest in climbing, biking, or doing any of the things that were important to them before.

Some forms of chemotherapy slow the advancement of the fastest-reproducing cells—like cancer cells, like hair. Alex’s body was perfectly smooth, completely open to the air and the gaze of the people surrounding him. He couldn’t help but think of the arête, of climbing it. A layback with the tips of his rock shoes carefully placed in the seams between bricks, maybe heel-hooking the corner for rest, a top-out at the roof. His mind always went back there, back to climbing, at the points where he felt the most stress. It made sense, then, that this is what would occur to him at the moment of his most blatant vulnerability. This highest of high exposures, despite not leaving the ground.

“I felt changed, different, invaded,” he said, about what the cancer treatment did to him. He knew it was a trivial vanity and so didn’t mention it to many people, but it was impossible for him to ignore. We are so conditioned in society to care about how we appear physically to other people that despite how Zen we are about the fallaciousness of valuing that, until it is rapidly and drastically taken from us, we cannot understand the strength of its grip upon our consciousness. For men, the gender roles associated with masculinity demand strength and require a stoic absence of sensitivity. To be weak, for any reason, jeopardizes one’s social designation as “manly.” Alex didn’t want to care so much about how he looked, but he couldn’t help it. He did. To him, it felt wrong; he was mindful of people whose cancer felt like a death sentence, and there he was, worried about his bald head, his bald chin. He wanted to show others a positive mindset, to tranquilize their worry with outward happiness, but he wasn’t happy. “Life is constantly inconsistent,” he said, another modicum of adage wisdom in the ether of a sad story. “I had to do something to recondition how I thought about what I looked like.” His illness forced him to become aware of these problematic things.

He called his friend Emily, proprietor of a studio in Fishtown, and agreed to what had been a jest between them for years. Alex was used to suring up his stomach against a scary climb. The only way to start a bold route was to start it. If something frightened him, he was headlong into the densest part of the fear before it could convince him to turn away. This would be no different. He was ashamed of his body, afraid of it. The best way to approach this was to do so the way he’d always approached climbing, to get deep into it. The class was titled Cancer in the Raw, and Alex would, for the first time, offer his torn body to be drawn by strangers, their charcoal and graphite and paint reproducing his deepest insecurities onto things as telling as paper and canvas.

On the day he was to model nude for the class, he thought of a million reasons why he should bail. He was used to vulnerability but of a different sort; at gravity’s whim he could protect himself—being careful, being mindful—but here, the outside forces could think their thoughts and draw their conclusions long before they drew their pictures. Sitting in his car in front of the studio, Alex fumbled through a text message explaining to Emily why he couldn’t come that day, when she knocked on the window of his car and enthusiastically waved him out. Text message unsent, he was committed.

The courage it took for Alex to enter that building felt similar to the courage he had to generate for facing the chemo that had left him looking like that. Psychologically, it didn’t make sense that facing an aggressive level of cancer treatment and sitting still, naked for a while, would call upon the same bravery, but Alex concluded that courage was one thing: we could compartmentalize it as much as we wanted, but courage was one thing. One singular thing. What changed were the circumstances in which we are asked to summon it.

He walked inside and accepted the proffered beer while waiting for the class to arrive. Nervously, he wandered around the studio, pretending to absorb the framed art. He fingered through the flyers left on the windowsill, ambled around the supplies in back, displayed a honed bravado as he spoke to Emily about what was to come.

When the class began to arrive, Alex didn’t know protocol. He wasn’t an artist, nor had he ever sat in a studio with a model. Of course he’d seen the television and movie scenes where naked people were drawn, but that didn’t still his discomfort at becoming the subject and knowing how to act. In natural form, Alex tried to neutralize his own awkwardness by talking to the arriving artists. He introduced himself, “So it’s me. I’m the guy. I’m the model.” One by one, the artists took their places.

Emily had Alex come to the back room in order to get ready. He thought to himself, “Do I just get naked here and walk out? Do I put on a robe and take it off when I get out there? What’s the standard here?” He decided it would be better to just get naked and walk out that way. Cold water. Jump on in. He disrobed and immediately thought, “Oh God, I’m naked.” There it was, the body he wasn’t used to and didn’t want. The twenty pounds he’d gained during treatment feeling as it was hanging from him; he skin, bereft of any hair, no more of the red that accented his paleness in what defined him.

Nevertheless, he walked out.

Alex walked to the platform at the center of the artists and said, “Well, I guess it’s time to start, because I’m naked.” Perhaps the exclamation was so atypical for the scenario or because it acknowledged to everyone present the social norm of clothedness that was then uniformly ignored, but his comment elicited a laugh from the artists. From him. They were ready. He stood still and was drawn and painted.

For the next two hours, Alex held poses for five minutes or up to twenty minutes. He tried to release himself from the expectations. The hardest part was stepping out; as the session went on, he felt freer. He had nothing left to hide, “You’ve got nothing up your sleeve; you’ve got no sleeves!” For Alex, there was fear of the moment but no fear in the moment. Yes, he thought, just like in climbing.

He realized that the class wasn’t about him. His cancer and insecurity brought about a sort of solipsism where he—like in the classroom—was the center of everything. But what was really true was the artists were there to improve their craft, to hone their own skills. They weren’t there to be critical of his body, to pity him; they were there to work on their craft. This was their training for a big climb and he felt embarrassed to have made it all about himself.

He wanted people to see the human body in an unfavorable form. As had been his personality all along, Alex ceased to think about how exposed and vulnerable he felt and instead thought of the others, the artists. Like what drew him to nursing, he began to see the class as a means by which he could help others achieve their own goals, “Being a nude model provided me the chance to let people view my body just the way it was. I could let people see exactly what the body could look like when it’s in a fight against cancer. I hoped that experience helped me to become more comfortable in my own body while giving the gift of art.”

When the two hours were up and he was back in his clothes, he had the opportunity to see what the artists had done, “I was completely shocked by what I saw. Beautiful drawings of what could have been anyone, yet I knew it was me. It was the first time since losing my hair that I felt any real beauty from my physical appearance. By looking at the drawings on the paper I came to a new understanding of myself. The way that I see myself isn’t the way that other people see me.”

What was most important, however, was not the drawings, it was that Alex decided to put himself into the scenario where he’d have to be vulnerable then introspective. He knew it was something he needed, no matter how scary the thought of it was, and so he did it. The class made him feel like a person, just like any other person. The cancer didn’t make it onto the canvas.

After the art class, Alex knew a new sense of confidence in seeing himself made powerful through the eyes of others. Staring out of the window, looking at the brick arête now after the class, he began to feel happy. Something just felt right—everything. “They were just sketches of a man. Not a single one of my insecurities were there.” This revelation was important; it showed Alex that even though the cancer and chemo took his physique from him, took from him how he knew himself, they didn’t take him. He could still be and would always be himself. If even reduced to nothing as he was drawn down towards death, he would still be Alex, and this new thought gave him purpose to walk out of that studio with confidence against his treatment as well as against the expectations of the world.

“The next day I needed to get a CT scan of my upper torso to look for blood clots secondary to lymphoma. I was having the testing done at the hospital I worked for. I didn’t wear my hat in the hospital. I didn’t wear my hat all day. I smiled, said hello to friends, and put myself into a machine that would look deep into my body. All of this looking at and into my body left me with a better sense of who I was. Just another person, trying to figure it all out.”

Alex felt more confidence in his ravaged body. He felt freer to own his circumstance. In the act of exposing himself in the most sincere form of vulnerability, to utter strangers, he instead found a cloak in which to sheath himself, to steady himself when considering his reaction to things he couldn’t control. It was a first ascent. Getting to a wall and finding the route that no one had, ever, climbed, plotting the course as the first person to ever climb that wall that way. Others had been diagnosed and struggled against cancer before, indeed, but this was Alex’s first ascent. This was his charting a new course, entering a foreign country, to find that bold new route and get on it—come what may.

Okay, he thought. Let’s go.