The Road that Led to Shelf Road | with Rick Thompson & Cricket

Posted by Holly Yu Tung Chen on 7th Apr 2021

Hi, it’s Cricket here, and welcome to Cracking the Crag! This series is brought to you by––uh, nobody, we’re not fancy enough to have official sponsors. Nevertheless, I would like to give a special shoutout to Fred’s espresso maker. This series wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for that mighty machine.

I had a chat with Rick “Rico” Thompson, the author of Sharp End Publishing’s bestsellers, Shelf Road Rock. Thompson hailed from the Northeast and began his climbing career in the New River Gorge in the golden age of American sport climbing. What was scheduled as a half-hour chat turned into a four-hour interview. “I’ve got so many stories that remain untold and unpublished,” says Thompson. Today, we reflect on the early 80s when Thompson had just discovered climbing. Rest assured, there will be a part two.

After developing over 300 new routes in the New River Gorge, Thompson finally turned his attention west.

“I was dating a gal who took me to Shelf Road. I was pretty psyched. Having read all about Shelf Road climbing, I knew who all the big players were,” Thompson suddenly threw his hands up in the air, “but when I showed up at Shelf, it was empty!”

“Where was everyone?”

“Rifle!”

When Thompson was a student at the University of Utah, he would drive past Cottonwood Canyon on his way home and look up at the beautiful granite outcrops. Sometimes his eyes would stray so much, and he’d have to swerve to avoid hitting the highway barriers. The cliffs were 200, 600, 800ft high, and he’d look for the tiny silhouettes of climbers on them. At the time, Thompson was a skier with no climbing experience. “But I was really getting into mountains,” he said. “I had read about the first ascent of Annapurna and became inspired to climb myself.”

Thompson moved back to Pennsylvania when he finished school and bought Royal Robin’s Basic Rock Craft. The little book taught all the basics, the knots, the belays, and rigging up a swami belt that would make any modern climber shudder. He found a guidebook to a local crag named Cooper’s Rock near his hometown of Sewickley. The guidebook was more a brochure than it was a book, a few pages of crudely drawn topos and a few lines of descriptions. He awkwardly hobbled up the rock face with a broken leg that day, having broken it during ski season, but “the hook was deep.” Thompson said the word deep with multiple “e” and drew it out.

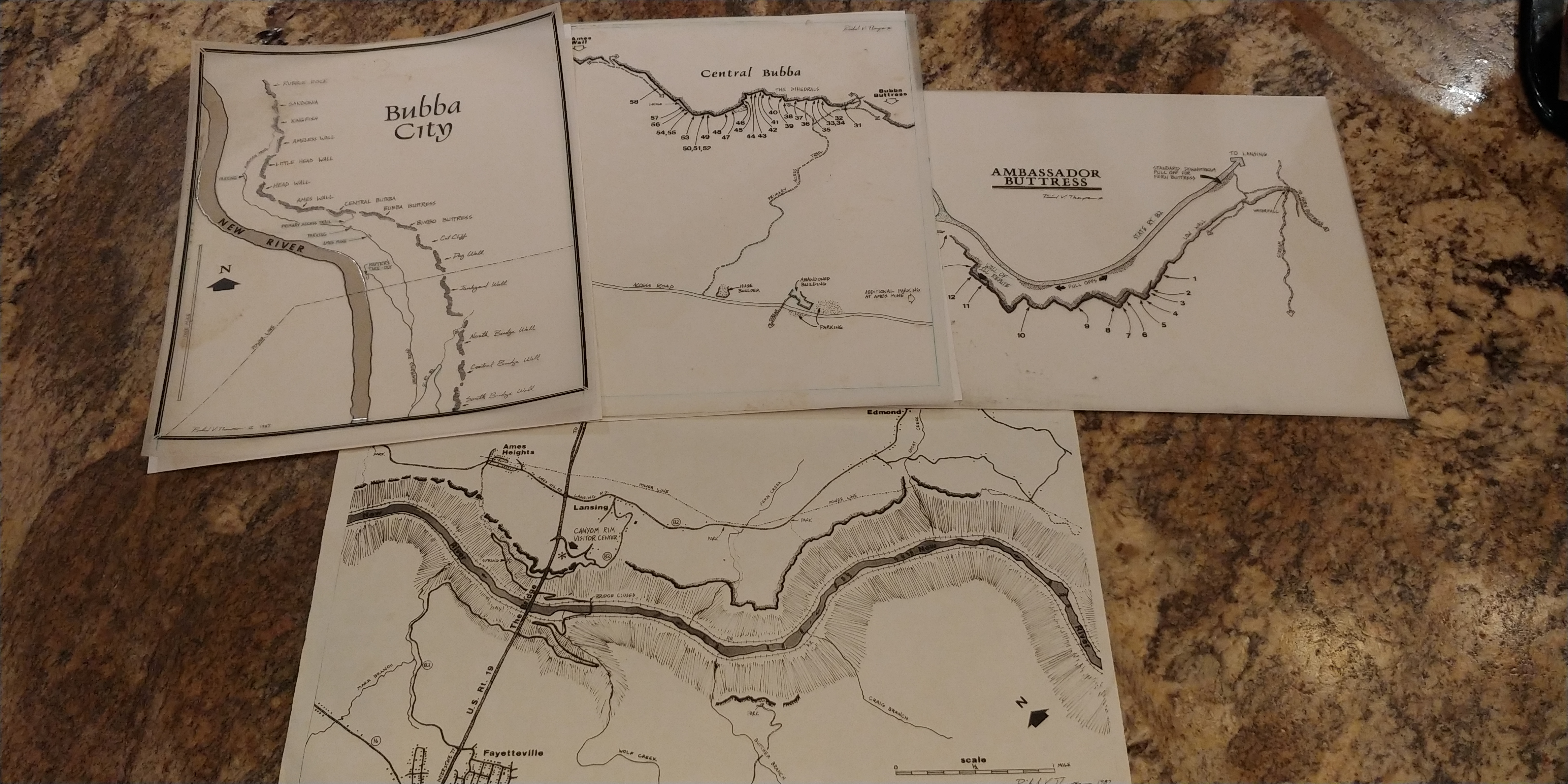

Thompson made his first trip to the New River Gorge in the middle of a muggy and stifling West Virginian summer in 1981. “It’s the kind of heat that sticks to you,” he said. The sky poured on them half the time, and it continued to through the summer, but Thompson went back every weekend and sought refuge under the prospect of untouched, bullet-hard sandstone. By 1984 he had a hand-drawn personal guidebook. Before drone footage and fancy cameras were available, Thompson would walk the cliffs with a compass, a notebook, and pencil, translating what he saw onto paper. His background in architectural design came in handy.

Before Lynn Hill was a world-famous climber, she’d come and hang out with Thompson. “Not that she doesn’t hang out with me now she is a world-famous climber,” Thompson laughed.

“Rico, this is the best rock in America,” Lynn would say.

“Eh, you really think so?” Thompson hadn’t traveled much at that point and was convinced the best rock was yet to be found. Now, after having climbed all over the country and the world, asking Thompson to pick out the best climbing in America would be pointless. “It is certainly among the best,” said Thompson; he thumbed his newest edition of Shelf Road Rock, “but the best rock is usually where your friends are.”

News traveled much slower in the 1980s. Your climbing news came from the big magazines, Rock and Ice, Climbing, and an old publication that has since gone out of print, Off Belay. “You read them like the Bible,” said Thompson. They had sections in them where first-ascensionists could submit new routes called the Basecamp Report. So-and-so did this at the Gunks, complete with a short description of the route. It was how word got around, and you could buy it at $5.59 an issue.

Thompson knew everything was changing. He knew the up-and-coming climbing areas seeing rapid development would become the areas that shape American sport climbing. Sport climbing was in a liminal state during the 1980s, halfway between a half-baked idea and a pipe dream—it was in the state of becoming. Bolts were still considered controversial, and many believed traditional climbing was the only way climbing should ever be done.

“We were just sport climbing weenies,” said Thompson, “I use to take all kinds of heat, but I knew, I just knew!”

The road didn’t bring Thompson to Shelf Road until the fall of 1994. When he arrived to find an empty stretch of high desert, he realized the trend had moved from vertical limestone to overhung limestone. Alan Watts, the patriarch of American sport climbing, had been watching the European trends very carefully during the 1980s. Thompson believes Watts probably, most definitely, had the first power drill in the US that was applied to the sport of climbing. Smith Rocks, Oregon solidified as the birthplace of American sport climbing, and suddenly, there was a mad rush to find new rock.

In 1988, Thompson had read all about Watts’ ventures at Smith Rocks, and that March, he bought the first power drill on the east coast. He took it to the New, batteries charged and brand new bits a-blazing.

“A Bosch Bulldog,” said Thompson, “I paid $225 for it, and that was a lot of money for a climber.”

Before electric drills, bolts had to be drilled by hand, and it took anywhere from one to two hours per hand-drilled bolt. With his new toy, Thompson put a bolt in the wall at an astounding 55 seconds. “The line was Mega Magic,” said Thompson. “It was the first drill-equipped sport route at the New, a beautiful 5.12c face climb, named after the Sportiva shoes and the magic of the drill.”

1988 was a whirlwind of a year for sport climbing at the New. Thompson's first guidebook for the New River Gorge, published in 1986, saw the area go from 35 established routes to over 400. The second edition, published in 1986, contained 1500 routes. Today, the New boasts over 1800 routes of every type of climbing imaginable.

“It was an amazing time to be a climber, a strange time too. We climbed other people’s routes occasionally, but we were focused on climbing new routes and putting up first-ascents just because we could.”

Richard Aschert took a drill to Shelf Road’s limestone in 1987, ten months before Thompson bought his Bosch Bulldog. Many think of Shelf Road as Smith Rocks’ younger brother, the second area to be developed as a sport climbing destination. Shelf Road had a handful of big players like Aschert, Dave Dangle, Darryl Roth, Bob D’Antonio, and Mark Van Horn. They had all gone out and bought a Bosch Bulldog. It was time when routes were transitioning from mixed routes to all-fixed routes.

Dangle was the man to innovate the cold shut to become a top anchor. Wielding them closed, he realized you could drill a bolt through it, and it would double as a bolt hanger. It didn’t take long for the original developers at Shelf to realize this method was not sustainable, and they stopped, but Dangle’s invention gave birth to the modern top anchor as we know them today. Some of the original Dangle cold shuts still exists around Shelf Road.

Smith, Shelf, and the New were hotbeds of sport climbing before it fanned out to places like 11-Mile Canyon and Wild Iris. The transition happened in the blink of a few years. By 1989 and the early 1990s, sport climbing had finally begun to settle in its current form. The emergence of climbing gyms completed the picture.

“But why was Shelf Road empty when you arrived in 1994?” I asked

“Everything had been climbed,” said Thompson.

“That’s not true. Shelf Road sees development even now,” I said.

“Everything that could be climbed had been climbed,” Thompson clarified. “A rancher owned the land where Cactus Cliffs are, and he chased the climbers off.”

Shelf Road grew silent for a while as places like Rifle stole the thunder. It wasn’t until 1998 when the Access Fund acquired the cliff band swath between the Bank and the Gym North until climbers were allowed to climb there again.

“Do you know how the Access Fund acquired the land?”

“Of course,” said Thompson. “I was one of Access Fund’s Founders.”

"Rico, we're out of time. But can we pick this back up? I think this is a story that needs to be told."

"Next week, same time?" Thompson asked.

"Sounds good."